Today's post is the third in a series from 4therapy.com (see link below), which looks at the psychological aspects of having neuropathy and other forms of chronic pain. This one looks at pain itself, what it does and why it happens. It also considers various options for tackling pain in the future - a very useful guide to understanding your pain.

A Pain Primer: What Do We Know About Pain?

Source: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

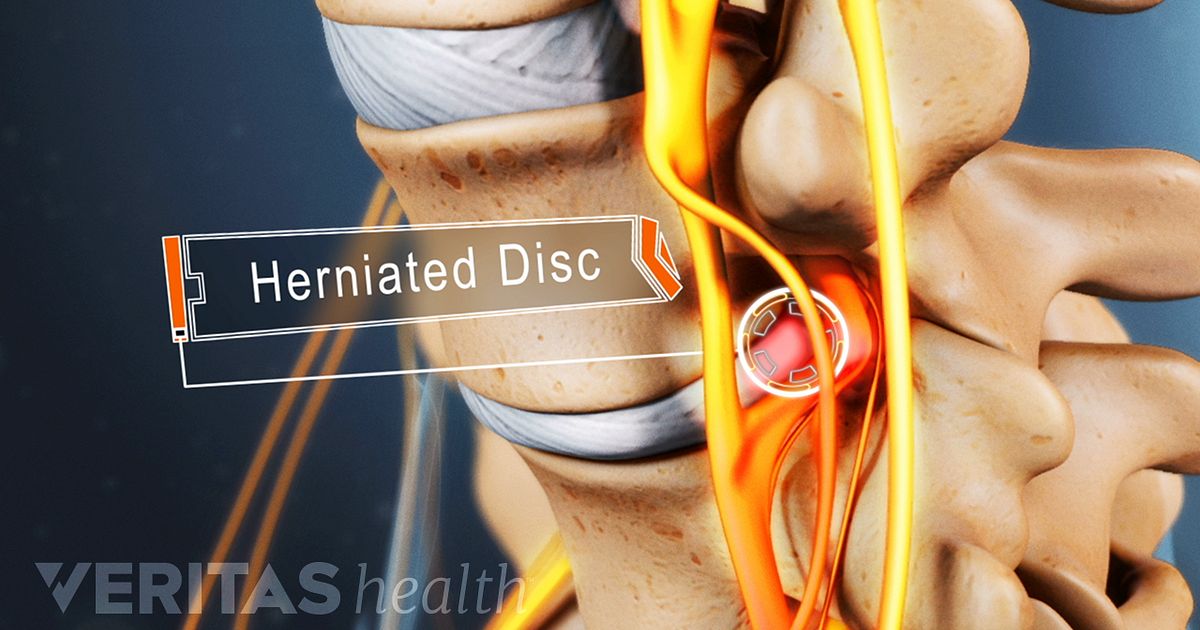

We may experience pain as a prick, tingle, sting, burn, or ache. Receptors on the skin trigger a series of events, beginning with an electrical impulse that travels from the skin to the spinal cord. The spinal cord acts as a sort of relay center where the pain signal can be blocked, enhanced, or otherwise modified before it is relayed to the brain. One area of the spinal cord in particular, called the dorsal horn, is important in the reception of pain signals.

The most common destination in the brain for pain signals is the thalamus and from there to the cortex, the headquarters for complex thoughts. The thalamus also serves as the brain's storage area for images of the body and plays a key role in relaying messages between the brain and various parts of the body. In people who undergo an amputation, the representation of the amputated limb is stored in the thalamus.

Pain is a complicated process that involves an intricate interplay between a number of important chemicals found naturally in the brain and spinal cord. In general, these chemicals, called neurotransmitters, transmit nerve impulses from one cell to another.

There are many different neurotransmitters in the human body; some play a role in human disease and, in the case of pain, act in various combinations to produce painful sensations in the body. Some chemicals govern mild pain sensations; others control intense or severe pain.

The body's chemicals act in the transmission of pain messages by stimulating neurotransmitter receptors found on the surface of cells; each receptor has a corresponding neurotransmitter. Receptors function much like gates or ports and enable pain messages to pass through and on to neighboring cells. One brain chemical of special interest to neuroscientists is glutamate. During experiments, mice with blocked glutamate receptors show a reduction in their responses to pain. Other important receptors in pain transmission are opiate-like receptors. Morphine and other opioid drugs work by locking on to these opioid receptors, switching on pain-inhibiting pathways or circuits, and thereby blocking pain.

Another type of receptor that responds to painful stimuli is called a nociceptor. Nociceptors are thin nerve fibers in the skin, muscle, and other body tissues, that, when stimulated, carry pain signals to the spinal cord and brain. Normally, nociceptors only respond to strong stimuli such as a pinch. However, when tissues become injured or inflamed, as with a sunburn or infection, they release chemicals that make nociceptors much more sensitive and cause them to transmit pain signals in response to even gentle stimuli such as breeze or a caress. This condition is called allodynia -a state in which pain is produced by innocuous stimuli.

The body's natural painkillers may yet prove to be the most promising pain relievers, pointing to one of the most important new avenues in drug development. The brain may signal the release of painkillers found in the spinal cord, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and opioid-like chemicals. Many pharmaceutical companies are working to synthesize these substances in laboratories as future medications.

Endorphins and enkephalins are other natural painkillers. Endorphins may be responsible for the "feel good" effects experienced by many people after rigorous exercise; they are also implicated in the pleasurable effects of smoking.

Similarly, peptides, compounds that make up proteins in the body, play a role in pain responses. Mice bred experimentally to lack a gene for two peptides called tachykinins-neurokinin A and substance P-have a reduced response to severe pain. When exposed to mild pain, these mice react in the same way as mice that carry the missing gene. But when exposed to more severe pain, the mice exhibit a reduced pain response. This suggests that the two peptides are involved in the production of pain sensations, especially moderate-to-severe pain. Continued research on tachykinins, conducted with support from the NINDS, may pave the way for drugs tailored to treat different severities of pain.

Scientists are working to develop potent pain-killing drugs that act on receptors for the chemical acetylcholine. For example, a type of frog native to Ecuador has been found to have a chemical in its skin called epibatidine, derived from the frog's scientific name, Epipedobates tricolor. Although highly toxic, epibatidine is a potent analgesic and, surprisingly, resembles the chemical nicotine found in cigarettes. Also under development are other less toxic compounds that act on acetylcholine receptors and may prove to be more potent than morphine but without its addictive properties.

The idea of using receptors as gateways for pain drugs is a novel idea, supported by experiments involving substance P. Investigators have been able to isolate a tiny population of neurons, located in the spinal cord, that together form a major portion of the pathway responsible for carrying persistent pain signals to the brain. When animals were given injections of a lethal cocktail containing substance P linked to the chemical saporin, this group of cells, whose sole function is to communicate pain, were killed. Receptors for substance P served as a portal or point of entry for the compound. Within days of the injections, the targeted neurons, located in the outer layer of the spinal cord along its entire length, absorbed the compound and were neutralized. The animals' behavior was completely normal; they no longer exhibited signs of pain following injury or had an exaggerated pain response. Importantly, the animals still responded to acute, that is, normal, pain. This is a critical finding as it is important to retain the body's ability to detect potentially injurious stimuli. The protective, early warning signal that pain provides is essential for normal functioning. If this work can be translated clinically, humans might be able to benefit from similar compounds introduced, for example, through lumbar (spinal) puncture.

Another promising area of research using the body's natural pain-killing abilities is the transplantation of chromaffin cells into the spinal cords of animals bred experimentally to develop arthritis. Chromaffin cells produce several of the body's pain-killing substances and are part of the adrenal medulla, which sits on top of the kidney. Within a week or so, rats receiving these transplants cease to exhibit telltale signs of pain. Scientists, working with support from the NINDS, believe the transplants help the animals recover from pain-related cellular damage. Extensive animal studies will be required to learn if this technique might be of value to humans with severe pain.

One way to control pain outside of the brain, that is, peripherally, is by inhibiting hormones called prostaglandins. Prostaglandins stimulate nerves at the site of injury and cause inflammation and fever. Certain drugs, including NSAIDs, act against such hormones by blocking the enzyme that is required for their synthesis.

Blood vessel walls stretch or dilate during a migraine attack and it is thought that serotonin plays a complicated role in this process. For example, before a migraine headache, serotonin levels fall. Drugs for migraine include the triptans: sumatriptan (Imitrix®), naratriptan (Amerge®), and zolmitriptan (Zomig®). They are called serotonin agonists because they mimic the action of endogenous (natural) serotonin and bind to specific subtypes of serotonin receptors.

Ongoing pain research, much of it supported by the NINDS, continues to reveal at an unprecedented pace fascinating insights into how genetics, the immune system, and the skin contribute to pain responses.

The explosion of knowledge about human genetics is helping scientists who work in the field of drug development. We know, for example, that the pain-killing properties of codeine rely heavily on a liver enzyme, CYP2D6, which helps convert codeine into morphine. A small number of people genetically lack the enzyme CYP2D6; when given codeine, these individuals do not get pain relief. CYP2D6 also helps break down certain other drugs. People who genetically lack CYP2D6 may not be able to cleanse their systems of these drugs and may be vulnerable to drug toxicity. CYP2D6 is currently under investigation for its role in pain.

In his research, the late John C. Liebeskind, a renowned pain expert and a professor of psychology at UCLA, found that pain can kill by delaying healing and causing cancer to spread. In his pioneering research on the immune system and pain, Dr. Liebeskind studied the effects of stress-such as surgery-on the immune system and in particular on cells called natural killer or NK cells. These cells are thought to help protect the body against tumors. In one study conducted with rats, Dr. Liebeskind found that, following experimental surgery, NK cell activity was suppressed, causing the cancer to spread more rapidly. When the animals were treated with morphine, however, they were able to avoid this reaction to stress.

The link between the nervous and immune systems is an important one. Cytokines, a type of protein found in the nervous system, are also part of the body's immune system, the body's shield for fighting off disease. Cytokines can trigger pain by promoting inflammation, even in the absence of injury or damage. Certain types of cytokines have been linked to nervous system injury. After trauma, cytokine levels rise in the brain and spinal cord and at the site in the peripheral nervous system where the injury occurred. Improvements in our understanding of the precise role of cytokines in producing pain, especially pain resulting from injury, may lead to new classes of drugs that can block the action of these substances.

http://www.4therapy.com/life-topics/chronic-pain/pain-primer-what-do-we-know-about-pain-2860